Isabella had brought a photograph with her to show her father-in-law. Heinrich von Angeli compared the two boys, who were now imitating a game of billiards on the parquet floor of his drawing room with umbrellas and three ivory balls, with this photograph taken last year. Giselbert, the middle one of the three, still looked like a boy in it, but had obviously now arrived in adolescence. His little brother Wolfgang, on the other hand, at thirteen years of age, was still the same handsome and happy rascal that the whole family had always loved. Years ago, he caused the family great concern when polio almost struck him down. But in the meantime, thank God, the illness had been cured and only his left leg remained a little thinner. He had proudly announced to him, the grandfather, that he had started playing tennis and wanted to become world class, at least as good as the American Bill Tilden. Both grandchildren were looking forward to the end of the school year and even more so to their trip to Hustopetsch in Moravia at the beginning of July to visit their cousin Cary Baillou. The two summer-tanned boys were quite at ease and lively in their conversation with him, even though they would have preferred to be at the Baden lido than here in his cool city palace in Vienna.

Meanwhile, Isabella looked around and first of all took a look at the kitchen. Then she inspected the bedroom and the bathroom, found everything very proper and was full of praise for the housekeeper. At Isabella’s request, Frau Gröschl had moved from Gmunden, where she had worked for the Cumberlands, to Vienna three years ago after the death of Bertha von Angeli. She had quickly found her feet here on the Wieden and had been running the household ever since. She benefited from the fact that the professor, whom she had known for a long time from his summer stays at the castle in Gmunden, was an extremely friendly and patient gentleman who would never have overwhelmed her.

When Isabella returned from her inspection round, she learned from her father-in-law that he would be receiving a visitor at any moment, but that she was welcome to stay. ‘But whether the two boys will feel comfortable in my mothball much longer, I don’t know.‘

’No, dear Dad,’ said the petite, still attractive woman in her mid-forties, whose hair, beautifully tied in a bun, was already beginning to turn silver, ’we’re about to leave because we want to catch the Baden tram at two o’clock. But please let me be curious about who is paying you a visit?‘

’A lady called Alice Schmutzer, you probably don’t know her. She writes features for the ‘Neue Freie Presse’. If I can still manage it, I would like to paint her portrait, while she wants to quiz me about what and how much a former court painter like me has experienced over the course of three quarters of a century.”

Isabella replies: ’Well, that could be quite entertaining. I know the name Schmutzer, isn’t there a painter called Schmutzer?‘

’Ferdinand Schmutzer, if that’s who you mean, an excellent etcher.‘

’I don’t know exactly what an etcher is or does, but if you call him excellent, he must be a true expert.‘

She now ordered her two boys to tidy up the parlour, handed them her jackets and was already leaving when a bright ringing sounded.

’Ah, my guests! Bella, please stay a moment longer, I would like to introduce you to them.

Alice entered, Angeli introduced the two women to each other, after which there was a few more minutes of conversation until Isabella urged ‘adieu’ and two boys said goodbye to their grandfather.

‘Nice boys!’ said Alice, as the door closed and Angeli invited her into the parlour.

He nodded and said, ‘Yes, they’re two jolly brothers! I have the feeling that the older one, whom they call Gi, will be a real handful one day, he’s already a sly old dog. But all three – there’s also the oldest, Heinrich, who is already turning twenty and is now doing his A-levels in Neutitschein – have been raised in an exemplary manner. And I understand that my daughter-in-law sometimes has to be strict too. She has been a widow for ten years and, God knows, it hasn’t been easy for her. Her mother, a Jordis-Lohhausen, helps, and of course I don’t stint either, because on my father’s side, from the Attems-Petzenstein, nothing can come, because they have nothing themselves. If I hadn’t bought so many damn war bonds, everything would be different – ‘ and with a sigh continued: ’ – or not. In the end, it all comes down to the fact that we shouldn’t have lost the war. But let’s not talk about that tiresome subject.”

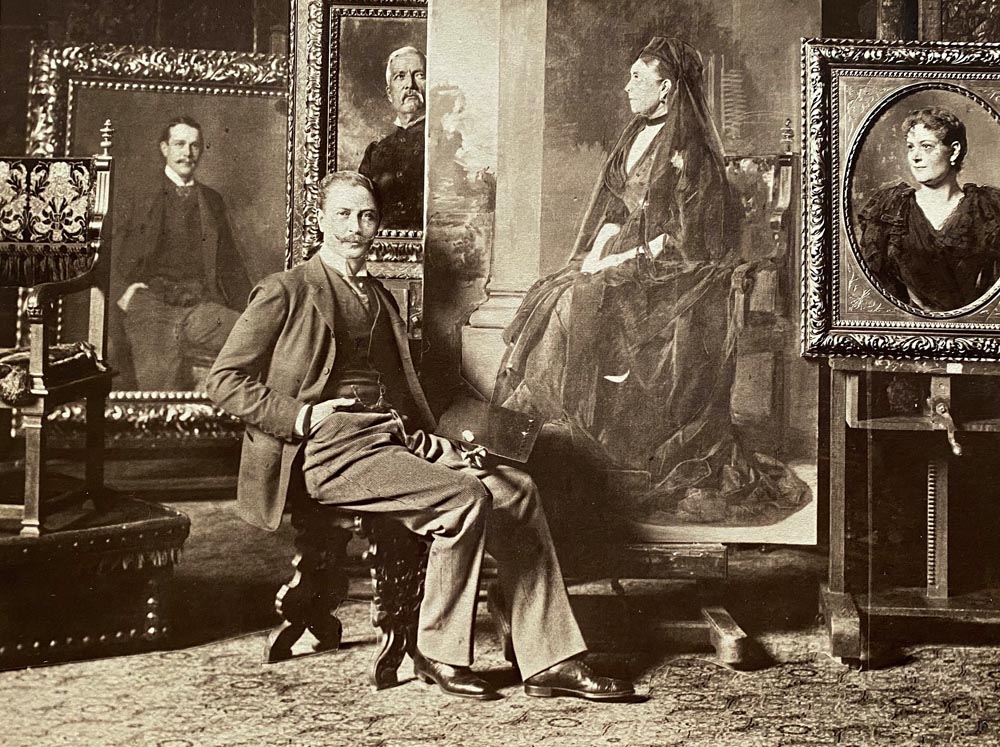

The painter paid Alice a compliment about her becoming costume and then showed her the chair where she should sit for the portrait. ’We are doing it here in the salon, it is bright enough and I save myself the trip up to my small, private studio, which I have on the upper floor. My former studio was at the Academy on Schillerplatz, up on the fifth floor, with excellent lighting. I was granted it for life by Emperor Franz Joseph and I could still claim it today without the need for imperial patronage. But I’m happy to do without the stairs up there. Now and then I work in my friend Fänner’s studio. Do you know him? He’s a sculptor. Despite his talent, he’s always had plenty of money, even during the war years, and I mean real money. And nothing beats a well-heated studio!

So, and here we cover the street-side window with tulle so that the light is softer, just the way ladies like it. But before I start with the first sketches, Frau Gröschl should serve us some tea.”

Alice was somewhat nervous. Suddenly she thought she was not in top form for the portrait after all; her hairstyle, her complexion, she urgently wanted to check everything again, but didn’t dare to ask for a mirror to check. Over tea and biscuits, they chatted about all sorts of trivial things, until suddenly Angeli felt the need to refer to an article in the May issue of the ‘Wiener Journal’, which he felt he could not withhold from her, as it tied in with their conversation a few days earlier. He handed her the newspaper:

“Please turn to page eleven. An interesting review, of course I read it a long time ago, but you will make me happy if you read the few lines that I have underlined out loud!‘

He handed the newspaper to Alice, who turned to the page and promptly found the clearly marked passage:

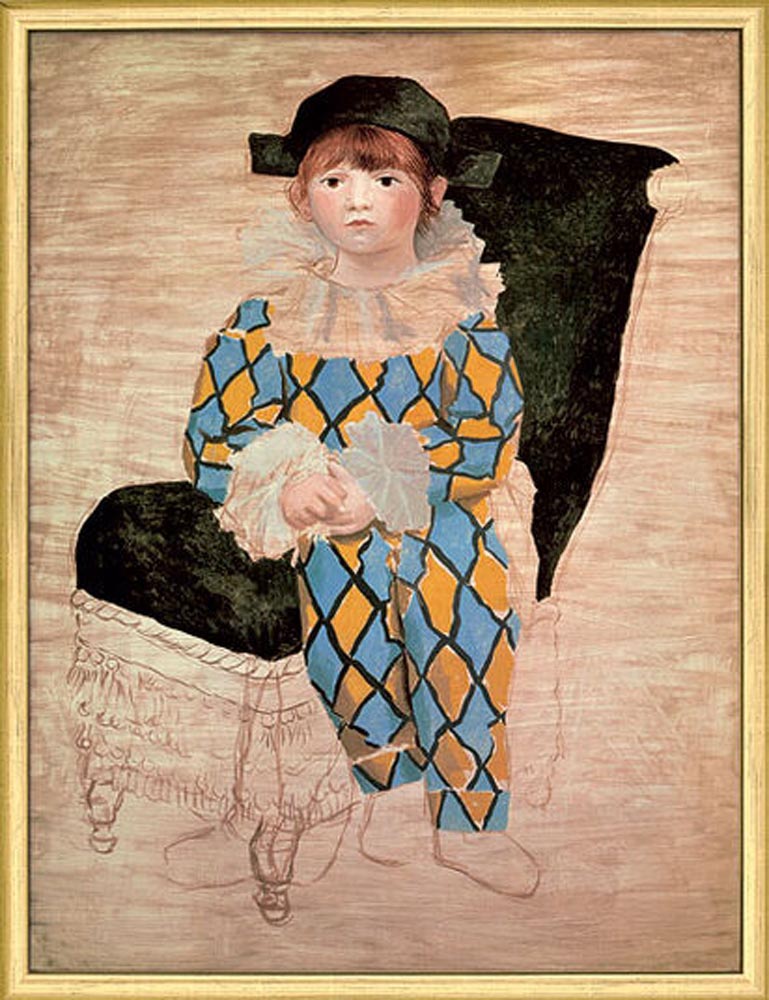

’Cubism, which until recently dominated the field of painting, is dying. No one cares about the wild leaps of the hot-headed geniuses anymore. It is a remarkable sign of the completely changed situation that even Picasso, the famous Pablo Picasso, who until recently was still a wild Cubist, is now appearing before the public in a completely different guise after a few years of silence. At the moment, an exhibition of Picasso’s latest paintings can be seen at the Rozemberg Gallery in Paris. The chalk drawings exhibited here, with their soft, harmonious, airy style, are as attractive as those of a 14th-century Florentine painter. And the same applies to the oil paintings, which, with their clear, richly coloured painting style and classical style, are reminiscent of the great masters of Italian fresco painting. But the case is not limited to Picasso; Severini, the Italian painter living in Paris who was one of the leaders of Futurism, also turned to the classics for advice, just like Picasso. This reorientation is in the air; this is also evident from the fact that the French Cubists, who have sought success in the wake of their Italian colleagues, have now started to paint sensible pictures again. The art dealer Rozemberg, who bought Cubist pictures by Picasso, Severini, Metzinger and their colleagues for thousands upon thousands of francs, recently admitted to a critic: ‘Ten years of Cubism and four years of war have led me to ruin.’ A collapse such as we are experiencing here is unparalleled in the history of painting.

She folded up the newspaper and said, ‘My husband is of much the same opinion. But he fears there will be many more leaps in the future.

Recently we saw pictures by modern French painters at the Würthle art shop.

It was interesting, there wasn’t a single Impressionist, but there were plenty of Expressionists, Cubists, Dadaists and even, imagine that, a so-called cylindrist called Fernand Léger. They really do go in all possible directions.”

Angeli replied, ’That may well be, but they are all experiments, I mean, and not much more. Only what remains will count, and only true mastery can remain. And I have collected quite a bit of that over the years, and I am always amazed by it. Please, before we get to work, take a look around at my modest collection.‘

With a small amount of effort, he stood up, leaned inconspicuously on the elegant stick with a silver knob, and escorted Alice along the walls of the parlour.

’There, please, a Tiepolo, just a sketch, but valuable because unsurpassable. An excellent seascape by Andreas Achenbach. The art history department would love to have this little Vinckboons, because it is said to be the work of the old Breughel. Or here, Jan Fyt, ‘Large Still Life with Hare’, first-class Flemish Baroque painting.”

Alice’s attention was drawn to a black-framed Holbein under glass, and she remarked: ‘A marvellous painting, it looks so familiar, I feel I should know it and I can’t help marvelling at finding it here.”

Angeli smiled: ’You have a good eye. Don’t worry, this painting is only a copy, but it has a special story behind it. I’ll have to go into more detail another time. But look, here is another special gem, an ‘Ecce homo’ by Salvator Rosa, a picture I really love!”

Alice was impressed by the collection of old masters, but was even more interested in the pictures painted by Angeli, all of which were framed portraits, on the walls and easels in the parlour and smoking room: early self-portraits, a picture of his fifteen-year-old son Viktor, whose sad story she already knew, then portraits of his mother and his wife, followed by a depiction of an adventurer with an oriental air and portraits of two strangers to her, one Henry Stanley, the other Alexandre Dumas, as Angeli explained.

When they finally arrived at the portrait study by the window, Angeli said: ‘There are a few more pictures upstairs in the studio, but we won’t go up there. Perhaps on one of your next visits.’ While he was laying out paper and pencils, he said: ’When I say that, for me, portraiture is still the highest form of painting, it may sound haughty or arrogant coming from me, because you might think I am referring to my own work. No, certainly not. I am referring to the works of all the great and true masters before us, of whom I am only one of many students. It is my conviction that significant portraiture culminates in the fact that whoever paints their contemporaries, paints time itself. And in doing so, they fulfil the true task of all art: to depict and capture the same time.

While he he had clamped a sheet of drawing paper onto the easel and was now putting Alice, who had taken a seat on a stool, in the best light.

“I’m getting quite pensive, which will probably bore you. But you are an artistic person and, on top of that, the wife of an important artist, so I’m taking the opportunity to say something.’ And then added with a grin: ‘Don’t be cross with me.’

‘How could I!’ replied Alice.

With strokes that were astonishingly confident for an 84-year-old, Angeli began to sketch the head of Alice. She did not move, not even when he repeated the drawing on a second and third sheet of paper, and after more than half an hour, apparently not dissatisfied, he put the pencil down. Meanwhile, he had continued chatting: ‘These are drawings that I still have to think about a little. The freehand sketches are the most important for portraiture; if they are accurate, then not much can go wrong in the execution in vinegar and oil.‘

Alice dared to ask, “Is that generally how you do portraits?”

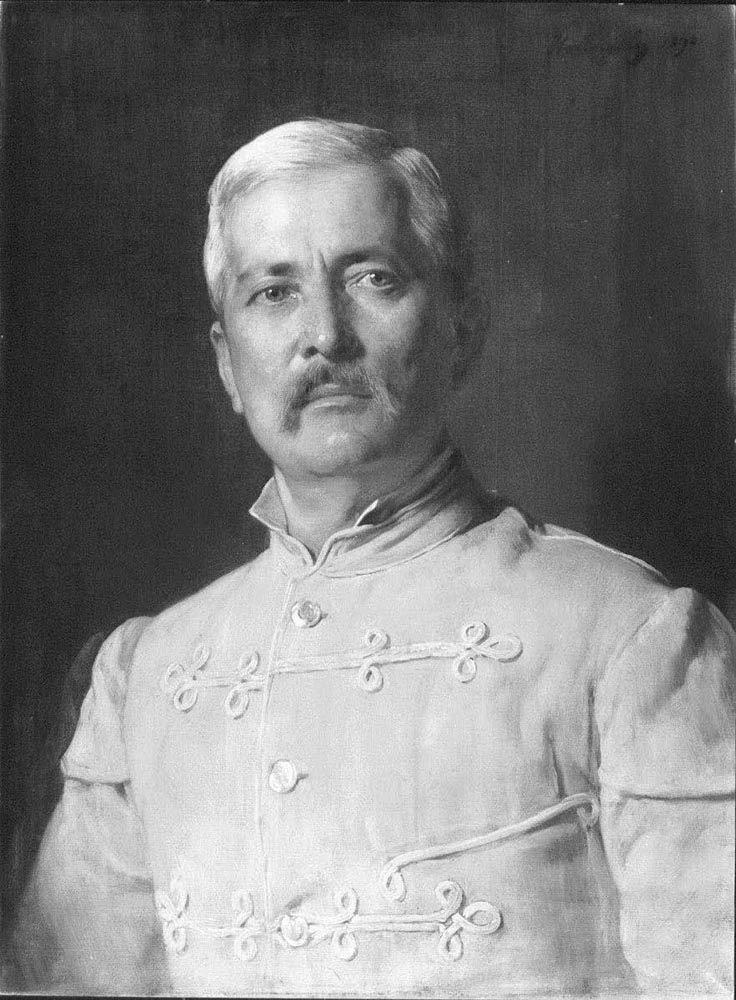

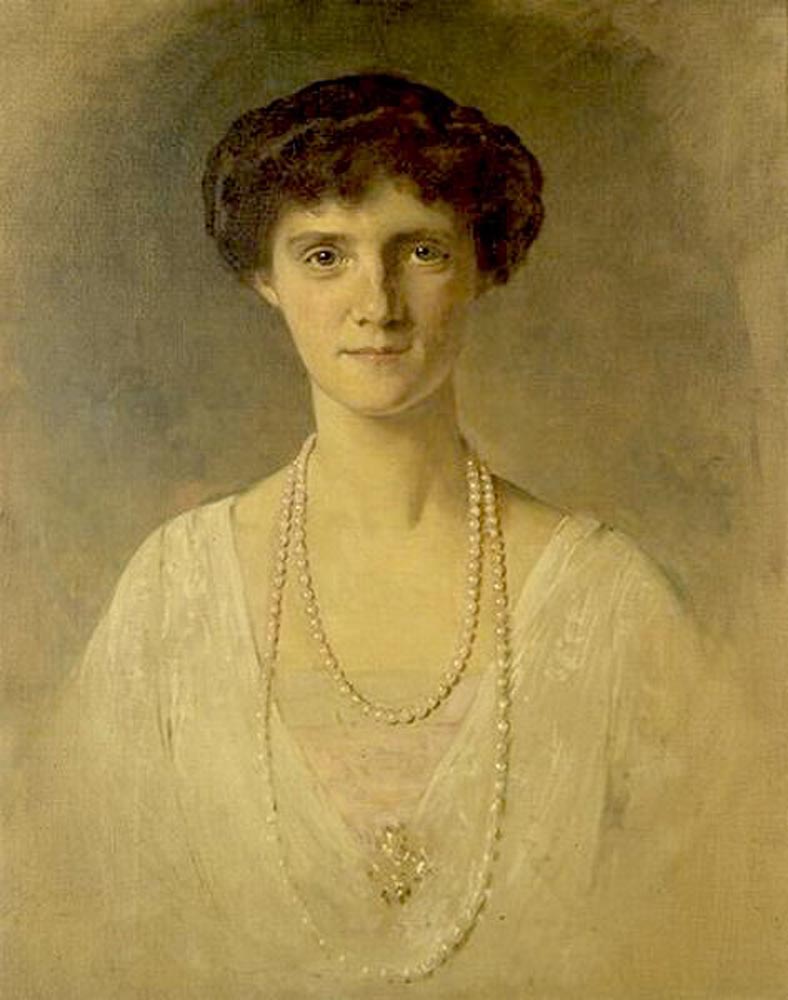

’Mostly yes. I know that your husband, who I consider a great master, likes to take a photograph and then translate it into an etching. That is a very effective method, but it is not for me, even though I have occasionally had a photograph taken of the people I am portraying. But, with two exceptions, I have never allowed myself to paint a photograph. In both cases, the subjects were the African explorers Stanley and Slatin. Queen Victoria, in whose service they were, held the two adventurers in such high regard that she absolutely had to have their portraits in her National Portrait Gallery. However, they had neither the patience nor the time for sittings. Since Her Majesty insisted on the painted likenesses of my hand, there was nothing left to do but paint them from photographs. I didn’t exactly dislike the first portrait of Stanley, but I wasn’t satisfied. So I painted a second portrait that pleased me and the Queen and now hangs in the gallery in Oxford. Heaven knows what I’ll do with the first one. The man’s fame hasn’t faded yet, so who knows, I might find a taker for it after all. It was similar with Slatin Pascha. When I met this warhorse, who is a true-bred Viennese, here in the city two years ago, he was mourning the death of his much younger, beautiful wife, who was also called Alice. I have his book ‘Fire and Sword in the Sudan’ in the library over there, in which he wrote about his sixteen years of captivity at the court of the Mahdi in Khartoum; Queen Victoria gave it to me, I could lend it to you.‘

’Oh yes, please. My husband would be interested in that, too,‘ said Alice, and asked, “Did you ever meet Henry Stanley in person?”

’Of course. A great explorer before the Lord, or rather before the Queen! He supposedly risked his neck in Africa. I didn’t find him particularly likeable, quite the opposite of Slatin Pasha, he was quite arrogant.

After she was allowed to move again, Alice asked the master:

‘Last week you already hinted to me how your own painting style also changed over the course of your life.’

“Oh yes, did I? I’m quite forgetful, you’ll have to excuse me.”

Alice: “You compared the portrait of Empress Zita with your work fifty years ago.”

Angeli put down his pen: ’Ah yes, that’s right. I painted her in Reichenau, in 1917, in my studio, which unfortunately is now empty and gathering dust.”

Alice interjected: ’Ah, what a coincidence! A few weeks ago, we saw a small oil painting by Wilhelm Regler that shows your studio out there. Painted by Emil Schindler, rather snappy, one could almost say impressionistic.”

Angeli laughed: ’Of course I know the picture too, and you’re not entirely wrong. Schindler must have thrown it onto the canvas at great speed, but you can’t say that it’s sloppy. It has something going for it, which is why he probably kept it. Only, the picture shows my earlier, much smaller studio, which is why it must be more than thirty years old, yes, definitely, because Emil Schindler, as far as I remember, died long before 1900. I liked him very much and honestly pitied him for the trouble with his wife, who Carl Moll has now married. One can only wish him: God bless you!‘

Angeli looked at Alice questioningly: “How did we end up with this picture?”

And she reminded him: “We were talking about the portrait of Empress Zita.”

’Ah yes. As I said, that was in the spring of 1917. Before the first session, my wife and I were invited by the then Archduke Karl to an elegant, but compared to earlier rather stiff supper at Villa Wartholz. In the past, before the war, we were almost regular visitors there in the summer, since we were neighbours – my home and the studio border on the imperial property and our son Gustav was close friends with Archduke Karl. The two contemporaries got along very well, did sports, went hunting and shared a particular passion, you wouldn’t guess it, for dog breeding! The two were so close that in 1912, when Zita gave birth to her first child, one could say the present-day crown pretender Otto, her husband was the first to send the happy news by telegram to our son Gustav.

After the assassination attempt on Franz Ferdinand in Sarajevo, of course, everything changed overnight, the previously affable Karl became a rather stiff archduke and heir to the throne, and two years later he inherited the throne of Emperor Franz Joseph and so on, well, we have witnessed the end of the sad story.

But back to the portrait: the young empress requested a simple execution, without pomp and splendour. She wanted the picture to have a private and intimate character, as it was intended as a surprise for her husband. I stuck to that and I much preferred it that way, because I found the formal portraits, as well as the photographs that were practically forced on the young monarchs after the enthronement, to put it politely, dreadful. To my utter amazement, Tom von Dreger was a favourite of Emperor Karl. But it didn’t take long, and didn’t even need the lost war, for everyone to see how flat and insipid the man painted him. His incompetence, dare I say, was transferred to the portrait and literally diminished Emperor Karl. Recently, I read in a self-portrait by Tom von Dreger that he was my protégé at the academy in the 80s. That’s true, but after such a drop in performance, I now feel uncomfortable.

I hope that this doesn’t come across to you as if I was offended that I never portrayed the young emperor. I certainly wasn’t, and I didn’t beg for commissions either.

Zita, on the other hand, I liked painting because she really is a strong character. And the sessions were entertaining, much as I had expected. However, she was only half and half satisfied with the portrait. She thought she looked too stern. And yet I find her to be just that: stern, self-confident, incredibly determined. I do not wish to judge her political influence on the events of her husband’s short reign, and certainly not on her role in the failed restoration attempt. But I will say this: she certainly held the reins much tighter than he did in his hands. In everything.‘

’Speaking of Emperor Karl,’ Alice said, ’I have brought something with me, namely a photograph that my husband took in 1917 and which he would like to show you. Kaiser Karl wearing a feathered hat, which, as Ferdinand told me, was a dazzling green.

Angeli bent over the picture, shook his head after a while and said: ‘It’s a good photograph, but what a ghastly headdress. You could almost call it a caricature of the young emperor. Why didn’t he object to it? Is there a lithograph of it?‘

Alice shook her head: “Actually, one was planned and my husband was prepared for a large print run, but the Obersthofmeister Montenuovo was against it for some unknown reason.”

’Better that way. People would have talked behind the shako’s back.’ Then he turned to Alice: ’Well, that’s it for today. You have been very well behaved. Thank you very much!‘

Alice had stood up and asked Angeli if he would like to satisfy her curiosity by telling her what the Holbein copy was all about, since she was so familiar with the painting from the Gemäldegalerie of the National Museums in Berlin.

’All right,’ said Angeli, ’but I have to say something first. The history of this painting requires an introduction that I hope you won’t find boring.

‘But of course not, I beg you!’

“Well, to start with, it is of course a copy, but not painted by me. It was given to me as a gift by a lady whose name you would have a hard time guessing: Empress Friedrich, the daughter of Queen Victoria. She was the wife of the German Emperor Frederick III, and they enjoyed a happy marriage for thirty years until he died of cancer in 1888.

Victoria, who in the following thirteen years of widowhood always only allowed herself to be addressed as Empress Frederick, was surprisingly talented at drawing and painting. I was introduced to her and her husband at the 1873 World’s Fair in Vienna. They saw portraits of me at the large art exhibition, were ‘quite taken with them’ and immediately gave me a number of commissions. During my first stay in Berlin, Crown Princess Victoria asked me to give her painting lessons. But don’t think that I was her only teacher. She also took lessons from Adolph Menzel, Anton von Werner, Franz von Lenbach and others, but I was truly her favourite – in all modesty! Her mother, Queen Victoria, also favoured me later on. No, seriously, we got along extremely well. Not only did she take my criticism of her painting well and really got better at it year after year. I can also claim that I understood quite well how to cheer up the often troubled woman with my stories and singing. God knows how often I was invited to an evening ‘dinner en famille’! And also to large evening gatherings, for example in the salon of Countess Schleinitz, where things were so tightly controlled in terms of German culture that I sometimes had to provide a little light entertainment. Once I even brought a quartet from the Vienna Male Choir to Potsdam, which was a huge success. There was such a mood there, almost a rush, that in the Kronprinzenpalais, long after midnight, there was still yodelling and singing.”

Angeli visibly enjoyed such memories, but he continued abruptly with a serious expression: ’Victoria had a lot to endure! Simply because, as a cosmopolitan, liberal-minded Englishwoman, she was constantly rubbing people up the wrong way in rigid Prussia, was ignored by her in-laws and was constantly at odds with Bismarck, the blood-and-iron chancellor. He had a deep mistrust of her, ‘the Englishwoman’, had her spied on constantly and ultimately managed to politically neutralise her husband, the crown prince. On top of that, the unfortunate delivery of her first child, the later Wilhelm II, who, after a breech birth, was born with a crippled left arm and, as it was said, a slight brain damage. And above all, the unspeakable misery that she and the crown prince had waited in vain for the throne because the old man, Kaiser Wilhelm I, did not want to step down. When he finally died, his son was terminally ill. And what was left for her? Actually nothing but bitterness for the rest of her life. The Germanising, jingoistic and militaristic policies of her son, Wilhelm Zwo, were justifiably her greatest concern, because they were directed not only against France but also against Britain, her beloved homeland. Victoria remained clear-headed and clear-sighted until a ripe old age, and she recognised the eminent danger of a military conflict between Germany and its allies France and England.

I was very close to the empress, whose many problems I knew well, until her death. Perhaps that is why I was so successful with the large painting showing the empress in her widow’s robes, which I consider to be one of my best paintings, if not the best of all. When I handed it over to her, that is, when I presented it to her, she was so touched that I received a copy of the Holbein painting from her in return, which she had created over many years of meticulous work. That was a very noble gesture, don’t you think?”

Alice agreed, of course, and said she would love to see the portrait of the Empress. Angeli suspected that it must be at Friedrichshof in the Taunus. The imperial widow had bequeathed it to her youngest daughter, along with the furniture and art collection. But he could gladly give her a lithograph, he just had to find it first.

Angeli added, ‘I was always grateful that Her Highness liked me and was fond of me. Victoria opened the doors to the Windsors for me, first and foremost to her mother, the Queen. And Victoria, I should also say, was such an educated and clever woman that it was a great pleasure to converse with her. She had an immensely broad mind and yet remained a simple, judicious woman. Had she and her husband remained on the German imperial throne, I am sure we would have been spared the Great War.

‘But for that to happen,’ Alice interjected questioningly, ‘Frederick would have had to stand up to Bismarck’s unrestrained politics if he had remained healthy. Would he have been strong enough?”

Angeli shook his head thoughtfully. ’Perhaps, perhaps not. Who can say? The crown prince was extremely popular in Berlin, a splendidly handsome man, not entirely free of Prussian militarism, but very different from his son. I think that with Victoria’s liberal ideas, which she would have forced him to stand behind, many things would have turned out differently, at least European politics after 1890 would have taken a different course. But unfortunately, Germany, just like our k. u. k. Monarchy, fell apart and Wilhelm II, judging by what one reads, has now become a passionate woodchopper in his Dutch exile at Doorn Castle.

‘Did you also paint the Crown Prince and later Emperor Frederick?’

“Yes , of course, several times in fact. The large state portrait apparently made such an impression that Theodor Fontane incorporated it into a touching poem!‘

’How so?‘

’Well, that’s definitely too long a story now, so we’ll spare you. I’ll lend you another book instead, a volume of poetry that includes this poem. It’s called ‘Last Encounter’. Maybe you’ll like some of Fontane’s other works too, which I really like, maybe because he and his works no longer correspond to contemporary tastes. A bit like me, isn’t it?”

Alice was embarrassed because she couldn’t think of a suitable reply, so she just shook her head and said, “Oh yes, I’ll be happy to read that.”

The painter then decided to end the session. Alice realised that he had grown tired, and yet he ended their visit with the most gracious kindness.

He did not want to accept the invitation to an evening supper at their place on Sternwartestraße, whenever he wanted, telling her: ‘That’s very kind, but as you can see, I’m walking with a cane. The lumbago the other day, I don’t even want to think about it. Climbing stairs has become difficult for me now, even though I do it at least once a day. Maybe later. And now summer is coming, so I don’t think it’s a good time to visit. We’ll make plans for the autumn.‘

’Are you staying in Vienna?‘ Alice wanted to know.

’For the time being, yes. But in August I plan to go back to Gmunden, to the hospitable Cumberlands. I love staying there and have a nice little room in the huge Victorian house, which the Welfs would call ‘cute’.

And, in case of emergency, as they say in England, I can rely on a good doctor in Gmunden who ‘

As a date for the next meeting, he suggested Friday, until he remembered that he had arranged to play whist with friends at Prückl’s:

“I cannot break this appointment, dear Alice, you must understand that! My friend, the building surveyor Doderer, would never forgive me. Let’s make it Monday. And, if you please, again at midday, you would be making me very happy. Dining alone is a bore.”