‘Ferdinand, listen, I’m going to read you a poem by Theodor Fontane and you tell me what it’s about. I’m curious to see if you know.’

The two Schmutzer sat on the bench in front of the house, looking out over the lush garden, structured by flowerbeds and a number of fruit trees that had already grown large. Above them still hung a few late curls of the light blue blossom of the wisteria, which Schmutzer eagerly awaited every year and which had made him happy again this year.

‘Go ahead!’ He asked Alice, who now tried hard to recite the poem that Heinrich von Angeli had recommended she read.

Last encounter

(14 June 1888)

King Oskar, from Mälar he comes, He crosses the sound, crosses the sea, Now he sees the coast: German land, heath, pine, , pine, Brandenburg sand,

And now avenues and palaces and alleys – He comes to see the dying emperor.

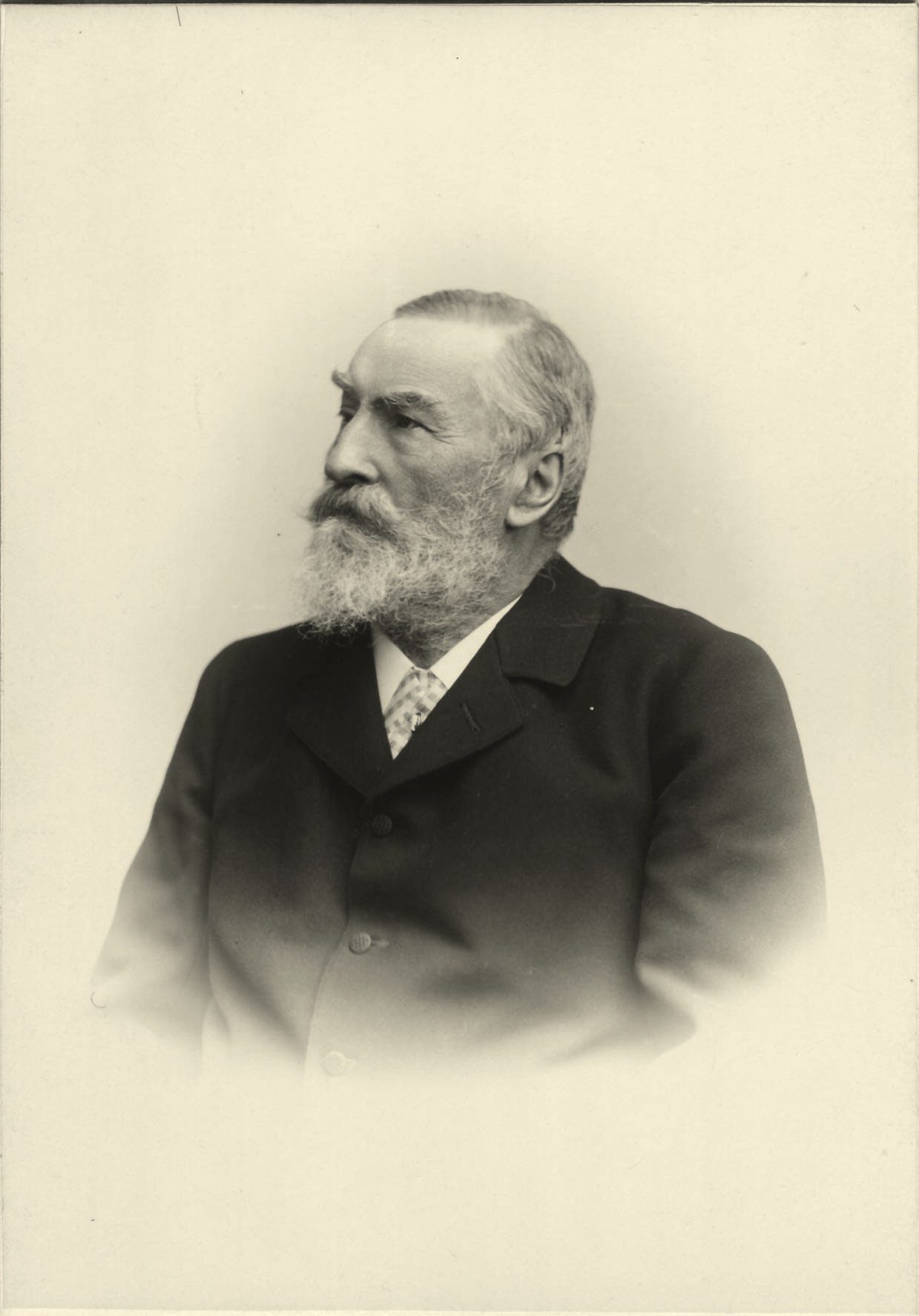

They report it to him. ‘King Oskar is here.‘ Emperor Frederick looked around as if searching. A glowing portrait hangs on the wall, his portrait by Angelis’ master hand, orange ribbon, medal, helmet decoration, Pasewalk cuirassier.

He looks at it and they understand his gaze :

‘Thus shall King Oskar be seen.’

And they put on him collar and cuirass, Upright once more the dying man, upright straight and gaunt and deathly pale –

King Oskar enters the marble hall, He wants to speak, but cannot,

A flood of tears breaks from his eyes. There stands his friend, in the yoke of misery, broken and yet still an emperor:

The sword to one side, the helmet in hand, Emperor Frederick stood before King Oskar.

Image once of greatness, beauty, luck, That is the last, that remained behind.

Mutely the king bows, and once again, And now for the third and – leaves the hall.

Alice looked up, and Ferdinand said after a moment, his head swaying thoughtfully: ‘Impressive, dear Alice. And the way you presented it, my compliments!‘

’But what do you think of the content?”

Ferdinand smiled: ’You might be surprised, but I happen to know this poem. And I know it very well because we had to learn it by heart in the seventh grade at the Theresianum. We had a German teacher who was perhaps a fan of Theodor Fontane, maybe, but in any case wanted to introduce us to contemporary poetry. And so I still know very well what the poem is about. But I have to look it up,

having forgotten that Angeli appears in it. I only now understand why.”

Alice, very excited: “But is the encounter historically documented? Did it really take place?”

Ferdinand was able to confirm: ’Oh yes, that’s as good as certain. The meeting between King Oskar of Norway and Frederick III, shortly before the latter’s death, did take place. In our German book at the time, there was a picture of the emperor printed on the opposite page from the poem. Unfortunately, I haven’t kept the book, but I can still remember it to some extent. A very simple reproduction, an engraving, from which I can now fairly well imagine the original painting by Angeli.‘

’Well, Ferdinand, you never cease to amaze me!”

To which he replied: ’ It is unlikely that the ‘dying emperor’, as it says in the poem, actually had himself dressed up in full regalia for this encounter, even if the Hohenzollerns maintained their obsession with uniforms even in and beyond their deathbed. Just before the war, as you recall, I was once in Berlin and stood in the mausoleum of the Potsdam Friedenskirche in front of the marble sarcophagi of Emperor Frederick and his wife Victoria. As a great warrior, he lies there in uniform, of course, with a huge sword on his chest. He was certainly a very capable general in 1866 and helped ensure that the Prussian army shot us Austrians in Königgrätz. But he was probably not a great hero.

From what I have read about him, Frederick, quite unlike his son, had a balanced character and was, not least through his wife, open-minded and much less Prussian than the Hohenzollerns in general are. It is quite conceivable that he and King Oscar were friends. They must have been around the same age. But there was one major difference between them: the Norwegian had been king for a long time, while Frederick, when he finally became emperor, had to gather for eternity after only 88 days. The way Theodor Fontane put it together with his painting of Angeli, you have to say: chapeau! That is great poetry. I don’t usually go in for such poetry, it’s too much pathos, but Fontane’s eulogy to the unfortunate Prussians has something, no question about it.”

Alice was thrilled to learn about the historical context in which the poem was set. Because yesterday Heinrich von Angeli had told her that the Vienna Men’s Choir, of which he had been an active member for many years, had included several Fontane poems set to music in its programme of songs, she asked her husband:

“Did you know that our friend is or at least was a passionate singer? He told me that when he was young he even had professional voice training, and not just from anyone, but from one of the best singing teachers in Vienna. After a while, he told him that he had come an astonishing way in terms of his singing. That pleased Angeli so much that he thought – and this is what he told me – that he would soon be able to whistle for all the painting! Of course he was joking!”

To which Schmutzer replied: ’Well, that would have been a shame, because a song, no matter how wonderfully it is sung, fades away as quickly as the wind blows. By contrast, one could almost say that Angeli’s paintings will endure forever. His portraits alone will be appreciated by historians for centuries to come, and no less so by art historians because of their high quality.

‘Yes,’ Alice agreed, ‘that’s true. If there is no catalogue of works yet, we should try to create one for the book project.

Ferdinand agreed with her and went on to muse: ‘A compilation of his, as you say, more than seven hundred pictures also reveals the stylistic decline of portrait painting towards the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of the twentieth century. I don’t mean that this is particularly evident in Angeli’s late work, but rather in a very general sense and as a reflection, as it were, of the social upheaval of which we are contemporary witnesses.‘

’No question about it,’ said Alice, ’Angeli did not lose his clientele. The fall of the ruling houses and the nobility surrounding them definitely meant the end of court painting, but not the end of demand for portraits by his hand. Of course, he can no longer work as much as he used to. But painting is still a pleasure for him, and it certainly gives him satisfaction.”

To which Ferdinand replies: ’I’m sure it does. At the same time, I can well imagine how he realises that many people who still have their portraits painted these days often want a completely different kind of representation of themselves. There’s no denying that people have simply adopted different viewing habits, and also look at themselves differently than they used to, to which photography has contributed. We only need to look at the pictures of Oskar Kokoschka that we recently saw at Würthle’s! The way he painted Karl Kraus! Hang this picture next to a portrait of Heinrich Angeli, and it looks like a caricature – and yet we have to admit that he has portrayed, or, if you will, characterised the venomous Kraus in the most excellent way.

“You’re right. And actually, Ferdinand, that applies to you as well, the way you work today: You are also moving more and more away from your classic style of etching and towards portrait photography, where you experiment with light and shadow, just like an avant-gardist. Right?”

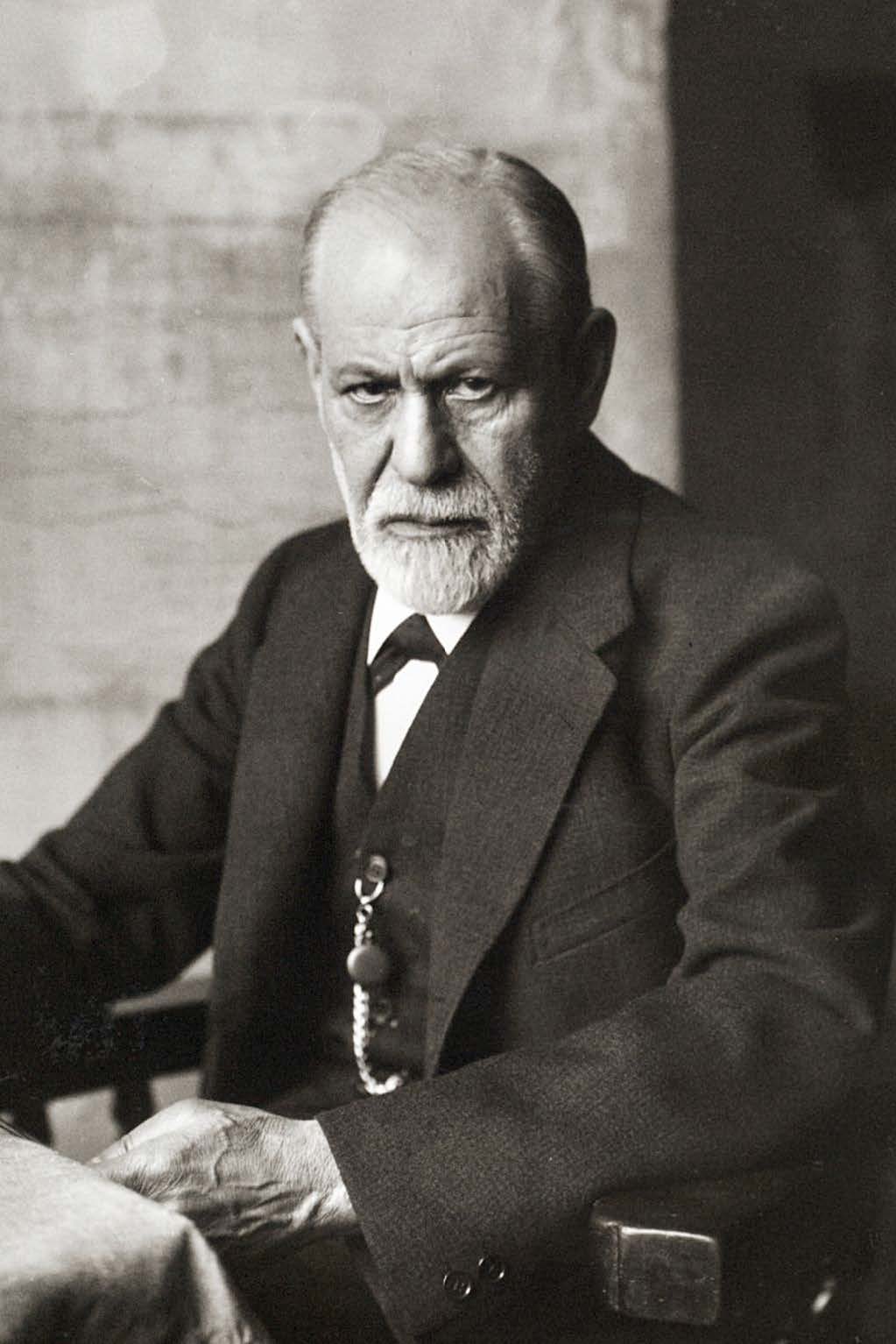

Ferdinand nodded: ’Yes. Only, I wish I was further along with it. If you take my portraits of Sigmund Freud and, more recently, Albert Einstein, they have been very well received, but they are still quite conservative. I would like to be much more abstract, more expressive, but that is a tightrope walk. Why? Maybe it’s because of photography itself, but it’s probably also because of me, that I’m much too set in my ways, don’t trust myself enough. And, to put it in prosaic terms, because there is no money to be made from experiments. I am now in my mid-fifties, we are established, accustomed to a comfortable income, especially in these uncertain times. But I feel a sense of dissatisfaction when I am limited to doing what I am good at.

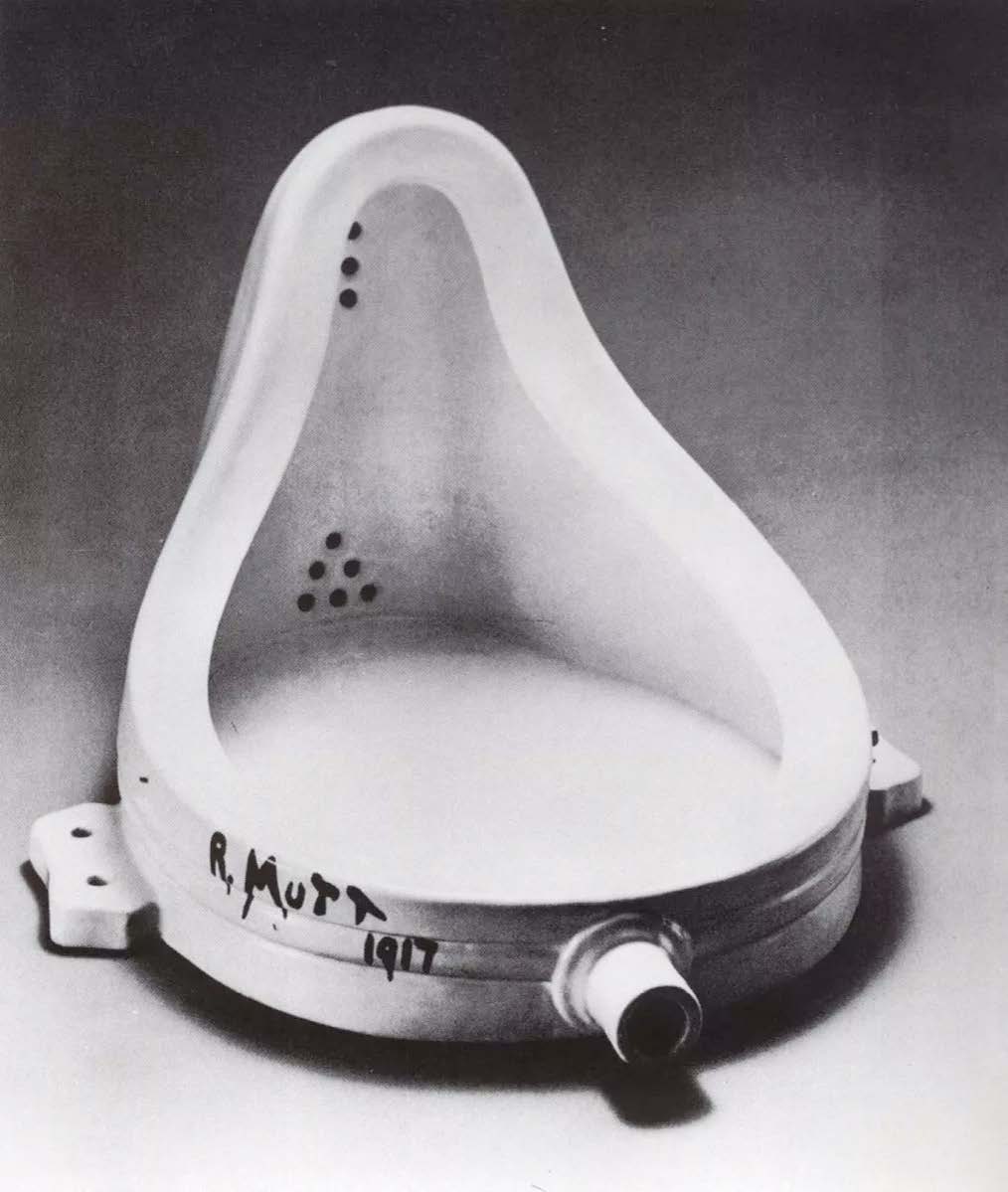

Our friend is much better off. Heinrich von Angeli is no longer burdened by the ‘course of time’. He is over eighty and has long since made his mark in art history. Even Dr Buschbeck will have to acknowledge that. And when it comes to the avant-gardists, especially the abstract artists, or a scandal like the one caused by a certain Duchamp in New York a few years ago, Angeli just shrugs his shoulders. Have you heard of this Duchamp?‘

’No, please enlighten me.‘

’Marcel Duchamp, a French artist, if I’m not mistaken, elevated a urinal, a pissoir shell, to a work of art at an exhibition of the ‘Society of Independent Artists’. Incidentally, this also shows that twenty years ago we Secessionists were nothing compared to a society like that.”

Alice, remembering a comment by Angeli, said: ’Obviously the provocations were important to you, but not just for the sake of provocation.’ Ferdinand agreed: ‘Exactly. What we did was supposed to be l’art pour l’art in the best sense, even if it didn’t always work out that way. Of course there were some of us who were primarily interested in provocation, which some of the audience liked very much because it allowed them to identify as progressive, in step, so to speak, with the artistic avant-garde. I see the difference between some of what is coming along now – and not only from the US, by the way – in that it was important to us to get the masses excited about art. And not just for the money, no. We strove for broad recognition. I wonder if that matters to the extremists among the expressionists. With the toilet bowl in question, they demonstrate the opposite. And so I have cobbled together a different explanation for myself.‘

’Well, I’m curious about that.‘

’It is undisputed that the senseless war not only caused immeasurable material damage, but also left behind a cultural devastation. Not only much of the existing beautiful art, but also its value and content have been lost in many cases. Some artists work through the meaninglessness and come to the view that nothing should count as art anymore. They proclaim nihilism, which reflects much of today’s sense of time. It is postulated: ‘We are at the end’.”

Alice interjected: ’Thank you very much! It turns into a permanent end of the world.

“Yes, and it goes as far as the eccentric. You don’t have to or shouldn’t necessarily share such a view. But people who have experienced terrible or horrific things and therefore have a different sensorium than we do, you have to understand and also allow them a different view of the world. Namely, a hopeless view of human society, which massacred itself in the Great War, has since lost its way in cold materialism, no longer recognises any order as in the past and uncritically accepts that everything together has become an inscrutable futility and senselessness. This is precisely where this state of mind comes from, which you can also call despair, in which everything becomes a farce, especially what wants to be considered art or a work of art and, above all, wants to be taken seriously as such. Then along comes someone like this Duchamp and thinks he has to tear down the entire so-called art business. Incidentally, the guy is supposed to be a very peaceful, affable person. And an excellent chess player to boot. ‘

Alice could only say, shuddering: ‘Good heavens!’

‘It’s obvious,’ Ferdinand continued, ‘that in the future we will be confronted with much more progressive art, which is already sloshing back and forth between Europe and America. Even in our little rump state, it can be seen that abstract painting and sculpture are slowly gaining in esteem in the visual arts. Anyone who wants to belong to something today has to be open to all directions. What is coming now will develop into an unprecedented revolution in the history of art, culture, education, and, for that matter, of civilisation as a whole. Perhaps I can express my expectations or fears differently, namely figuratively: whereas in the not-so-distant past, art came along like a broad, mighty stream, today it branches out into countless tributaries and channels, in which innumerable, mostly self-proclaimed artists splash around, experiment, succeed and, above all, want to attract attention. With one goal: to be contemporary!”

Alice: “I think art dealers are contributing to this, and I’m thinking of Würthle here.”

Ferdinand shook his head: ’I’m not so sure about that, my dear. Of course they support and promote one or the other, but dealers don’t make art movements any more than windmills make the wind.

‘I think it’s all very exciting,’ said Alice, putting her hand on Ferdinand’s shoulder and saying pensively, ‘Believe me, it really means a lot to me that I am able to experience Heinrich von Angeli during this period of upheaval, as casual as he is. In his reflections on the present, he is not in the least unworldly and expresses some interesting criticism of the spirit of the age. But never venomous or bitter. He couldn’t be, because his whole nature is one of noble serenity, and he always has a twinkle in his eye and a pun on his tongue. That rules out maliciousness. Well, you know him!”

Schmutzer nodded in agreement: ’You said you’re going back there next week. Maybe I could pick you up and take the opportunity to visit the grand seigneur again.

Alice was thrilled: ‘Yes, do that, great!’

Then she quickly told her husband the little episode in which Angeli scared off the German Emperor Wilhelm I. It was about fifty years ago, soon after the Franco-Prussian War, when he was summoned to Potsdam to paint a large portrait of his Majesty, naturally in all his splendour. For the king – he was not yet emperor at the time – the full breast of medals was of great importance. For Angeli, however, there were too many medals and so, for the sake of a better overall impression, he virtually dropped some of them under the table, so to speak. The grumpy majesty took offence to this and therefore demanded that they be completed. ‘Do you want me to really put the grafflwerk on?’ Angeli asked him, which made the Prussian king ask what a grafflwerk was. “Well, the order, Excellency.” Wilhelm was not at all amused by this Germanisation, and he deprived the painter, who had become very popular at the Hohenzollern court, of his favour for the rest of his life, but that didn’t matter much to Angeli. He was only sorry that he had not told his royal highness what had once happened to Emperor Franz Joseph, the higher-ranking colleague of his in matters of rank, because that would have been a good way to illustrate the difference between the Prussians and the Austrians. According to Angeli, the Austro-Hungarian anecdote goes like this: in a village somewhere in the monarchy, a Landwehr company is parading in front of Franz Joseph. As the emperor walks past them, he notices a small man whose uniform is adorned with a remarkable number of medals. ‘Where did you earn all of these?’ the monarch asks. The man replied: ‘Like everyone else, I got the big one after the manoeuvres in 1859. The second one was for 25 years of service in the volunteer fire brigade, the next one I won at the last curling competition, and the really big one I shot myself at the parish fair.’